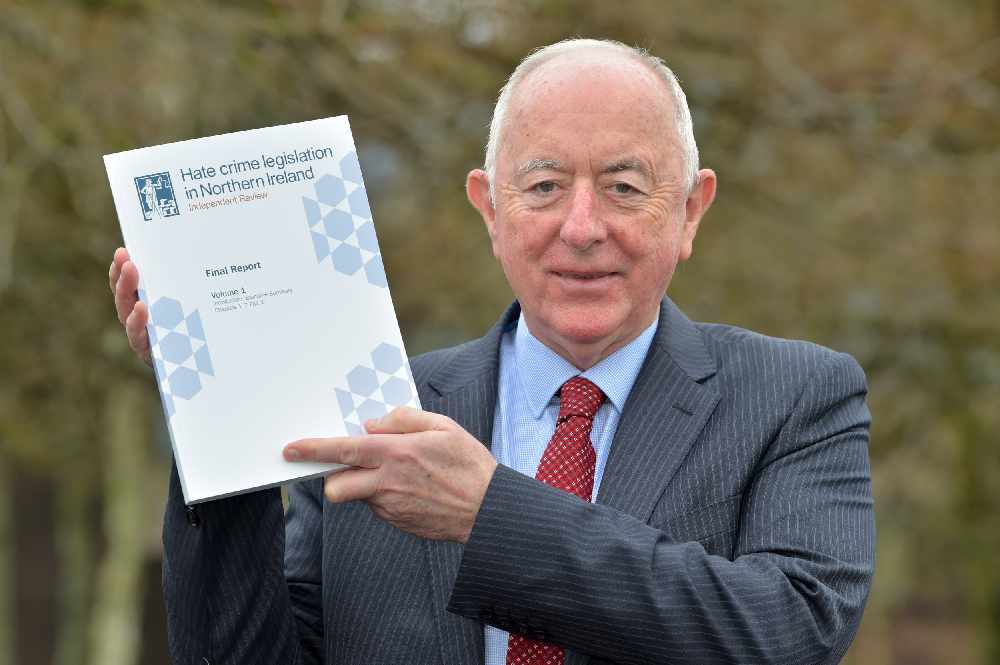

By David Young, PA

The definition of a hate crime in Northern Ireland should be expanded to include gender-motivated offences, a judge-led review has recommended.

Intensifying levels of abuse directed at women, both online and in person, justifies the legislative move, Judge Desmond Marrinan said.

The recommendation is part of a proposed major shake-up to address failings in the legal approach to hate crime in the region.

If adopted, Northern Ireland would be the first part of the UK to add gender to long-standing protected characteristics for defining hate crime motivations, such as religion and disability.

England, Scotland and Wales include transgender as a protected characteristic.

In his review, commissioned by the Stormont executive, Judge Marrinan recommends Northern Ireland should also add transgender to its legal definition, but urged it to be broadened further to include all crimes with a gender-based motive.

He said the internet had led to “dreadful trolling” of women, particularly those in politics and other positions of power.

“They are attacked ruthlessly and aggressively, and sometimes tragically,” he said.

“The attacks that come at them mercilessly online get translated into real life, such as the dreadful murder of Labour MP Joe Cox a couple of years ago because of her views on Brexit.

“There is a wealth of information that women are frequently assaulted – and they sometimes can be assaulted or attacked for other reasons – but very often it’s an assault on them because they are women.”

Characteristics presently protected under the law in Northern Ireland are race, religion, sexual orientation and disability.

Judge Marrinan has proposed that age, sex/gender and variations in sex characteristics are all added to the definition.

He also urged that sectarianism is legally defined as an aggravating factor.

The judge said the current system in Northern Ireland, whereby sectarian is dealt with as a religious issue, does not adequately capture the scope of sectarianism or reflect that it touches on nationality and political and cultural identity.

At present there is a lack of specific hate crime legislation in Northern Ireland.

Hostility against one of the protected characteristics can be factored in when a judge passes sentence on someone already convicted of an offence.

Judge Marrinan recommended a fundamental reorientation of this approach and proposed that hate motivation should be factored in at the start of the criminal justice process.

He proposed a new “aggravated” tier of offences to enable police and prosecutors to add hate crime motivation to any criminal offence.

That means someone accused of assault could be charged with a standard assault or an aggravated assault on the basis of it being motivated by “hostility, bias, prejudice, bigotry or contempt” against one of the protected characteristics.

Those convicted of aggravated charges would face stiffer penalties.

“It would be a complete change,” said the judge. “It would be a sea change in terms of attitude, because it would mean the police, for example, would have to take the hate element into account when investigating the crime.”

The judge also dealt with the issue of online abuse.

He said there is an urgent need for greater regulation of social media companies, including a requirement for a more robust registration system for users.

However, the judge acknowledged the Northern Ireland Assembly is limited in its powers to act, given it is a reserved matter.

He urged MLAs to either lobby the UK Government to take robust action or ask it to devolve responsibility for the issue to Belfast.

Judge Marrinan also examined the issue of hate speech as it applies to the offence of stirring up hatred under public order laws.

He said the director of public prosecutions should be personally involved in any decisions to prosecute such offences, given the need to ensure the rights of freedom of expression are protected.

The judge said he had sought to ensure all his recommendations reflected the need to protect free speech, noting that religious groups that had voiced concerns of a “chilling effect”.

Judge Marrinan said his overall conclusion was that the law in Northern Ireland is inadequate and change is needed.

“I’m quite satisfied, having spent all this time and consulted with over 65 organisations and many, many victims, that hate crime law such as it is in Northern Ireland is largely ineffective,” he said.

“That’s the core finding from this lengthy review. It is failing victims. There is massive underreporting of hate crime, perhaps 80% or more of such crimes are not reported to the PSNI (Police Service of Northern Ireland).

“And one reason that has been stressed time and time again with me by victims is that they don’t believe even when they do report it that it’s taken seriously.

“They don’t see results in court and they come away – even if there is a conviction – they come away very dissatisfied.”

31 arrests made by police investigating disorder in Northern Ireland

31 arrests made by police investigating disorder in Northern Ireland

Further five arrests made by police investigating disorder

Further five arrests made by police investigating disorder

Gun pointed at man during vehicle hijacking

Gun pointed at man during vehicle hijacking

American woman faces court charged over fatal crash outside N Ireland hotel

American woman faces court charged over fatal crash outside N Ireland hotel